Behind the Dragon Gate: Environmental Injustice in Chinatowns

Vibrant shades of red, bold calligraphy, the pungent smells of durian fruit or fresh fish, and the inextricable feeling of being in another world are all sensations that tourists experience when visiting Chinatowns across the United States. Beneath the red and gold glitter, however, the conditions for those living in the Chinatowns are less enchanting. From substandard housing to hazardous working conditions and school locations, Chinatowns prove to be not only unglamorous, but also, in many ways, unsafe. These ethnic enclaves are seeded in a deep history of ghettoization which have evolved into additional environmental injustices that continue to affect residents on a daily basis. The concept of environmental justice defines the environment to include public and human health concerns, and sees the environment as the setting in which people (predominantly people of color) “live, work, and play.”[1] Through showing a history of dismissiveness toward Chinatowns and Chinese immigrants across the country, I argue that environmental injustices have necessitated Chinatown residents to become the greatest advocates for their own safety.

This paper is broken into three sections, first analyzing the motives for the creation of Chinatowns and establishing a history of discriminatory practices towards Chinatown residents. I will then discuss how the existing power dynamics and systems of oppression continue to entrap immobile immigrants and have established the current conditions in Chinatowns, highlighting instances of health concerns, including asthma frequency and workplace toxin exposure. This paper will conclude by drawing upon the work of Asian American leaders in order to create more environmentally just living conditions.

~A Problematic Past~

Though Asian immigrants are often seen as recent arrivals to the country, the United States has a long history of Chinese immigration, and likewise a long history of discrimination and oppression against Chinese people. In the mid 19th century, nearly 40,000 Chinese citizens fled the faltering Qing Dynasty rule and sought the shores of San Francisco.[2] The 1849 Gold Rush left many Chinese immigrants in California hopeful of stumbling upon some of the buried treasure, but it was the opportunity to build the Central Pacific Railroad which created the first large permanent influx of Chinese people in California.[3] Poor Chinese immigrants were willing to work for lower pay, driving down wages across the state, which in turn increased animosity towards Chinese immigrants.[4] Throughout the 1800s, discrimination was formally set into law by exclusionary law, barring Chinese people from U.S. citizenship, land ownership, fishing in state waters, interracial marriage, and eventually even coming to the United States with the 1882 Chinese Exclusionary Act.[5]

Less formally, the creation of Chinatowns was another way of enacting discriminatory practices on Chinese immigrants. White Americans, for the most part, did not want to live among or work with the Chinese. Connie Young Yu, a Chinese-American historian and writer based in San Francisco suggests that during the late 1800s, “any building adjacent to one occupied by Chinese was rendered undesirable to white folks, and caused many landlords to hold out inducements to white tenants and refuse any and all offers from Chinese.”[6] The establishment of Chinatowns served as a way of congregating Chinese immigrants together and removing the “yellow problem” from direct contact. The increasing resentment towards Chinese immigrants forced them in less desirable and less competitive fields and pushed Chinatowns towards the more tolerant metropolitan areas.[7] Early depictions of these first Chinatowns were of exotic and dangerous scenes, and they were given the labels dirty and crime-ridden.[8] As anti-Chinese sentiment escalated in the latter part of the 1800s, these labels actually proved beneficial in keeping many white Americans out of the area. Most of the immigrants did not know the laws or the language and felt a need to stay together as hostility grew. For them, Chinatowns became a place of limited sanctuary from potential violence.[9] By the 1880s, however, Chinatowns were subjected to repeated acts of arson, forcing communities to uproot and reestablish themselves elsewhere.[10] Issues of race were most definitely involved in the lackluster responses by the San Jose fire department after the burning down of three different Chinatowns. Community members eventually established their own hydrant system, in case of fire, since they could not rely on the city’s support.[11]

On the other side of the country, Chinese immigrants established the Washington D.C. Chinatown for similar reasons of community building and protection.[12] This Chinatown sought relocation, not at the hands of arson, but because of forced evacuation by the federal government in order to build the Federal Triangle project in 1929.[13] Just over forty years later, the D.C. Chinatown was once again impacted by urban development. This time, Washington’s first convention center displaced a number of the neighborhood’s permanent residents and their businesses, leaving many older residents in destitute situations.[14] This perception of the D.C. Chinatown as a disposable community continues to haunt the area today. Duane Wang, the unofficial “mayor of Chinatown,” believes that “this history has contributed to Chinatown’s lack of growth because it created an uncertainty about the future.”[15]

Public dismissiveness towards Chinatowns comes in many forms. While the obvious demolition and relocation of Chinatowns is detrimental to the communities, simply ignoring them have harmful consequences, as well. This can be demonstrated by the 1981 struggle against the lack of garbage clean up in New York’s Chinatown. The trash situation in the Chinatown was problematized in September of 1981 in the opinion section of the New York Times (pictured above).[16] As mounds of trash clogged the already cramped streets, residents of the New York Chinatown took action. Community leaders met with an assistant health commissioner, compiling a list of over 50 restaurants and stores that desperately needed garbage services.[17] It was not accountability on the state’s part, but proactive behavior of the residents that got the Health Department to certify that the garbage at the businesses posed a health hazard.[18] Only then did the city finally begin to pick up the trash. While this was a victory, over 30 years later garbage build-up remains an issue in the New York Chinatowns. A New York Times article from 2006 cited litter, broken sidewalks, and other sanitation issues as top concerns for residents of the Chinatown.[19]

Public dismissiveness towards Chinatowns comes in many forms. While the obvious demolition and relocation of Chinatowns is detrimental to the communities, simply ignoring them have harmful consequences, as well. This can be demonstrated by the 1981 struggle against the lack of garbage clean up in New York’s Chinatown. The trash situation in the Chinatown was problematized in September of 1981 in the opinion section of the New York Times (pictured above).[16] As mounds of trash clogged the already cramped streets, residents of the New York Chinatown took action. Community leaders met with an assistant health commissioner, compiling a list of over 50 restaurants and stores that desperately needed garbage services.[17] It was not accountability on the state’s part, but proactive behavior of the residents that got the Health Department to certify that the garbage at the businesses posed a health hazard.[18] Only then did the city finally begin to pick up the trash. While this was a victory, over 30 years later garbage build-up remains an issue in the New York Chinatowns. A New York Times article from 2006 cited litter, broken sidewalks, and other sanitation issues as top concerns for residents of the Chinatown.[19]

~Current Conditions and Complications~

While the United States often acknowledges a discriminatory past, much of the current rhetoric on racism remains stuck in a black and white polarity, ignoring the current plight of Asian Pacific Americans.[20] This bias against Asian Americans as the “successful minority” even translates into scholarly work where Chinatowns are pictured as “thriving zones.” Wen, Lauderdale, and Kandula argue that “unlike the traditional concept of the inner city ethnic enclave, typically perceived as socioeconomically deprived urban neighborhoods concentrated with immigrants with little advanced skills and poor English proficiency, these ethnoburbs [Chinatowns] are characterized by high levels of education and affluence, a strong presence of residents with professional or managerial jobs, Chinese-owned business districts, high levels of Chinese participation in local politics, and a clear within-community social stratification.”[21] This purported success of Chinatowns is disproved by examining the current health and safety risks for the residents of today’s Chinatowns. Unfortunately, the effects of racial discrimination remain alive as environmental injustices in Chinatowns across the country.

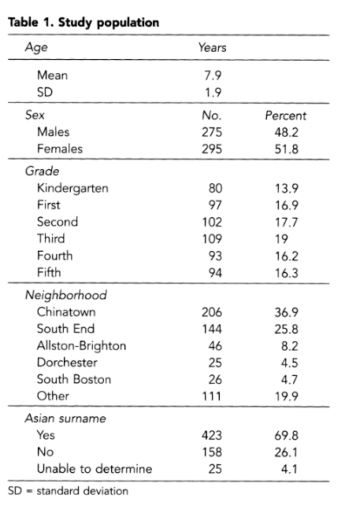

Chinatowns’ locations in primarily highly metropolitan areas has most definitely affected the air quality and exacerbation of asthmatic symptoms in children residing there. A study done within the Boston Chinatown indicated that 16% of the children had been diagnosed with Asthma, and roughly 3% showed symptoms but had not been diagnosed.[22] This statistic is contrasted with the [then] national rate of 5.6% of children between the ages of 5 – 14 being affected with asthma.[23] While minority residents of the inner-city are at higher risk for asthma, the children of the Boston Chinatown are particularly susceptible due to the limited access to healthcare and reliance on non-fluent parents, as well as facing a disproportionate amount of environmental hazards including air pollution, secondhand smoke, noise, construction, and trash.[24] Since the 1950s, massive highway constructionhas increased vehicle volume in the area, and likewise the number of traffic injuries. Moreover, the elementary school is at the southern border of the Boston Chinatown, adjacent to these two major highways – I-90 and I-93. A 2003 study by Tufts University School of Medicine suggests that “it is possible that the air pollution that surrounds the school is contributing to the prevalence and/or morbidity at the school.”[25]

While asthma is a particularly large problem for children, risks in the work environment are huge issues for the adults in the community. Exposure to these harmful conditions are less escapable for Chinatown residents than other minorities in blue collar jobs because they often live and work in the same place.[26] Many Chinese immigrants work for restaurants, small shops, and most notoriously, in sweatshops hidden in Chinatowns. Over half of all textile and apparel workers in the United States are Asian women. Garment workers in sweatshops face increased exposure to fiber particles, dyes, formaldehydes and arsenic, leading to high rates of respiratory illness.[27] A study conducted in San Francisco’s Chinatown showed that the restaurants, too, had dangerous environmental conditions with 82% lacking fully stocked first-aid kits, 52% lacking antislip mats, 37% lacking adequate ventilation, and 28% lacking adequate lighting.[28] According to a survey of restaurant workers, 95% earned less than a living wage, 50% made less than minimum wage, and only 3% received health insurance from their employers.[29] These hazardous conditions have called on environmental health agencies to enforce stricter regulations and incentives to prioritize safe working conditions.

As well as the work environment, other elements of daily life, including housing and dining, also hold components of environmental injustices for those in Chinatowns. Housing is a basic environmental issue because of the poor, substandard living conditions in tenement buildings. The walls are often lined with lead paint and the buildings are vermin infested, negatively affecting the health of residents.[30] Too often, poor tenants are not aware of the adverse consequences of lead exposure, or if they are they lack the power or resources to take appropriate action. Lead exposure becomes an issue in relation to dining, as well. A study conducted by the American College of Medical Toxicology found that the prevalence of lead-contaminated ceramics was far greater in Chinatowns than in Chinese communities outside of the Chinatown.[31] Exposure to lead-contaminated ceramics and possible consumption is especially concerning in a community that isn’t frequently tested for lead poisoning. Eating and drinking from lead-contaminated ceramics could leach into food and liquids and become a severe health risk.[32] The methods of gathering food for Chinese immigrants also pose environmental health concerns. Due to tradition and poverty, many Asian immigrants fish in waters with high mercury levels and other contaminants.[33] There is no adequate warning signage in non-English languages, though, leaving consumers (children and pregnant women in particular) unaware of the health concerns.

The worries of the Brooklyn, New York Chinatown’s residents clearly illustrate the idea that “health concerns of all kinds are exacerbated by poverty, language barriers, immigration status, culture, and the need for acculturation.”[34] In this area, 28% of residents live below the federal poverty level, and only 13% of adults aged 25 and older hold a college degree.[35] Many residents reported difficulty paying rent and bills, and working long hours for low wages in poor work environments in order to do so. While the majority of these jobs come with no job security or health insurance, workplace discrimination is rampant.[36] Residents cited the physical environment of this Chinatown as problematic, as well, highlighting neighborhood crowding and congestion, dirty streets, and safety concerns related to burglary and theft.[37] Due to the high number of undocumented immigrants or non-English speaking immigrants, seeking professional medical help is oftentimes dangerous or impractical. These marginalized statuses require Chinatown immigrants to resort to family members’ advice or traditional practices instead of receiving the medial attention necessary. When asked what could be done to improve health in Brooklyn’s Chinatown, many community members mentioned a personal responsibility to regular exercise, good nutrition, and avoiding smoking. They also mentioned state obligations of keeping the environment clean, providing a health hotline in Chinese, and increased health education initiatives, including lectures, brochures, and meetings with parents.[38]

The environmental injustices for this population are due to issues “primarily on occupational health issues and the injustices associated with being limited English speaking populations and immigrant populations.”[39] The same factors that contribute to the sources of the environmental problems are the same ones that entrap Chinese immigrants in these environmentally hazardous jobs and neighborhoods. One resident from the Washington Chinatown, Wendy Lim, recalls, “I think that the reason why we moved to Chinatown was probably because of English limitation. My mom didn’t know English, and I guess my dad knew a little bit of English. . . But I think the main reason why we lived in Chinatown was because of the language barrier.”[40] In addition to difficulties with language and cultural acquisition, poverty confines people within Chinatowns as well. Those seeking to leave are prohibited by the high cost of property in these large cities, making little outside of the Chinatowns affordable.[41] It is important to note this racial segregation and confinement within Chinatowns also occurs on a voluntary level. Chinatowns offer immigrants the ability to remain close to family members, stay in contact with a larger Chinese community, and retain a sense of familiarity.[42] The option of mobility for some residents, however, should not excuse diminished living standards. Under all circumstances people staying in Chinatowns should be afforded safe living conditions.

~Asian Activism~

The bamboo ceiling, fostered by the common conception of Asians as passive non-risk-takers is extremely inhibiting for Asian Americans in the workforce when seeking raises and promotions.[43] This passivity stereotype is disproved by Chinese immigrants’ long history of fighting for their environmental security. From the establishment of Chinatowns in the mid 19th century, the residents have been forced to take proactive stances, such as creating their own hydrological systems, making their voices heard about issues of garbage and sanitation, and collaborating with other groups in order to promote safer living conditions. This activism continues today in the form of street science, community mobilization and organization, and the creation of environmental coalitions.

Established in the mid 1970s, the Chinese Progressive Association (CPA) has been an integral factor in advocating basic immigrant and worker rights, as well as increasing standards of health and housing.[44] Their mission is to achieve social and economic justice for Chinese- Americans through working with other communities, providing educational, advocacy, service, and organizing programs that raise the communities’ living and working standards.[45] In 1996, the CPA learned that Chinatown in New York City had one of the highest levels of diesel pollution in the city and of the high correlation between exposure to diesel particulates and asthma.[46] The CPA , volunteers from the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance (NYCEJA), and multilingual college students collaborated together to create a survey to draw attention to the issue of asthma in the Chinatown. The results of the survey showed that nearly everyone was “very concerned about the environment and wanted to do something about it” and that about one in five households reported having a person with asthma living there.[47] The study also showed that central Chinatown, an area with a higher concentration of traffic and commercial activity, had a higher concentration of residents with asthma.[48] This information was then used as a tool of organization, creating an asthma health fair in Chinatown and putting pressure on the EPA to conduct more environmental testing in low-income residential areas. This case highlights the need of both statistical and human elements in environmental justice struggles, as well as the necessity of the whole community joining together in the fight for a healthier environment.

In the San Francisco Chinatown as well as east coast Chinatowns, there have been successful organization efforts against development projects, using the language of environmental racism.[49] One success story is of the Boston Chinatown which is located between two medical institutions that were seeking to expand their parking garages. Though a business deal was signed, residents organized rallies, petitions and community meetings which drew the attention of the state environmental agency. The state mandated that the hospitals study the impact the garage would have on air pollution, traffic, and open space/recreation.[50] The request was quickly withdrawn.

Similarly, the Philadelphia Chinatown faced the threat of intrusion in 2000, when Mayor John Street announced his intent to build a Major League baseball stadium in Chinatown.[51] In response, the Stadium Out of Chinatown Coalition formed, arguing that the neighborhood would be destroyed from traffic congestion, air pollution, and noise and disruption from construction.[52] The community conducted their own studies and threatened to take legal action through environmental and civil rights lawsuits until the project was halted.

Lastly, in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, a sludge treatment plant was proposed adjacent to a primarily Latino community as well as the nearby Chinatown. These two groups joined in coalition, raising concerns for facility related health risks and increased air pollution emissions. The coalition also highlighted the hypocrisy of Democratic Mayor David Dinkins’ actions. As the first non-white mayor in New York City, his campaign targeted the support of people of color, but this proposal contributed to environmental racism. The Sunset Park sludge treatment plan was later withdrawn due to this community action.

These stories of success as well as the establishment of several organizations focused on issues that affect low-income Asian immigrant populations provide a hopeful ending to an otherwise disheartening situation. The Campaign to Protect Chinatown of Boston, the Asian Pacific Environmental Network (APEN), and the Chinatown Justice Project of the Committee Against Anti-Asian Violence (CAAAV) have all been integral in bringing present day issues to light and fighting on behalf of this uniquely marginalized community. Surprisingly, the APEN is the only organization in the United States that focuses exclusively on Asian environmental justice issues.[53] Even before the birth of these organizations, Chinese immigrants’ dedication to their communities and environment through communal advocacy was remarkable. To appreciate the deep history of this group of people, it is critical to understand that the United States’ history of racism does not exist in a black and white polarity. Discrimination has very much impacted the lives of Asian immigrants, as well. This racism lives on through environmental injustices that can only be reversed by proactively addressing the harm that has been done. While efforts of communities and environmental justice organizations have certainly won some critical battles, more work is needed to ensure safe living environments for residents of Chinatowns nationwide. With elaborate marble gates, vibrant night markets, and an undeniable outward charm, Chinatowns have for a long time been visible and captured our attention. It’s time that the people living there become visible, too.

Bibliography

Baxter, R. Scott. 2008. “The Response of California’s Chinese Populations to the Anti-Chinese Movement”. Historical Archaeology. 42 (3): 29-36.

Chinese Progressive Association. Last modified 2008. Accessed May 5, 2014. http://www.cpanyc.org/About%20us.htm.

Gaydos M., Bhatia R., Morales A., Lee P.T., et al. 2011. “Promoting health and safety in San Francisco’s Chinatown restaurants: Findings and lessons learned from a pilot observational checklist”. Public Health Reports. 126 (SUPPL. 3): 62-69.

Gilmore T., O’Malley G.F., Lau W.B., Vann D.R., et al. 2013. “A Comparison of the Prevalence of Lead-Contaminated Imported Chinese Ceramic Dinnerware Purchased Inside Versus Outside Philadelphia’s Chinatown”. Journal of Medical Toxicology. 9 (1): 16-20.

Hathaway, David, and Stephanie Ho. 2003. “Small but Resilient: Washington’s Chinatown over the Years”. Washington History. 15 (1): 42-61.

King, Haitung, and Frances B. Locke. 1987. “Health Effects of Migration: U.S. Chinese in and outside the Chinatown”. International Migration Review. 21 (3): 555-576.

Lee, Mae. 2004. “Clearing the Air in Chinatown: Asthma advocacy stems from resident-driven research”. Race, Poverty &Amp; the Environment. 11 (2): 41-42.

Lee, T., D. Brugge, C. Francis, and O. Fisher. 2003. “Asthma Prevalence Among Inner-City Asian American Schoolchildren”. Public Health Reports. 118 (3): 215-220.

Mosenkis, Jeffrey. “Finding the bamboo ceiling: Understanding East Asian barriers to promotion in US workplaces.” PhD diss., THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO, 2011.

Ramirez, Anthony. “In Chinatown, Ugly Trash, but a Pretty Place to Put It.”New York Times (New York City, NY), April 1, 2006. Accessed April 20,2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/01/nyregion/01chinatown.html.

Ruskin, P. “Pungent Chinatown.” New York TImes (New York City), September 26, 1981, Opinion. Accessed May 9, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/1981/09/26/opinion/l-pungent- chinatown-027834.html.

Sze, Julie. 2004. “Asian American activism for environmental justice”. Peace Review. 16 (2): 149-156.

“The City is Picking Up Garbage in Chinatown.” 1981.New York Times (1923-Current File), Dec 16, 1. http://ezproxy.macalester.edu/login? url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/121633749?accountid=12205.

Thein, Khin, Kyaw Thuya Zaw, Rui-Er Teng, Celia Liang, and Kell Julliard. 2009. “Health Needs in Brooklyn’s Chinatown: A Pilot Assessment Using Rapid Participatory Appraisal”. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 20 (2): 378-394.

Wen, Ming, Diane S. Lauderdale, and Namratha R. Kandula. 2009. “Ethnic Neighborhoods in Multi-Ethnic America, 1990–2000: Resurgent Ethnicity in the Ethnoburbs?” Social Forces. 88 (1): 425-460.

Wu, Diana Pei. 2011. “Asian Pacific Islanders Made Statistically Invisible”. Race, Poverty &Amp; the Environment. 18 (2): 62-65.

Young Yu, Connie. 1981. “A History of San Francisco Chinatown Housing.” Amerasia Journal. 8 (1): 93-110

Zhou, Min, and John R. Logan. 1991. “In and out of Chinatown: residential mobility and segregation of New York City’s Chinese”. Social Forces. 70 (2).

1 Julie Sze. 2004. “Asian American activism for environmental justice”. Peace Review. 16 (2): 149.

2 David Hathaway and Stephanie Ho. 2003. “Small but Resilient: Washington’s Chinatown over the Years”. Washington History. 15 (1): 42-61.

3 Scott R. Baxter. 2008. “The Response of California’s Chinese Populations to the Anti-Chinese Movement”. Historical Archaeology. 42 (3): 30.

4Scott R. Baxter, “The Response of California’s Chinese Populations to the Anti-Chinese Movement”, 31.

5Scott R. Baxter, “The Response of California’s Chinese Populations to the Anti-Chinese Movement”, 32.

6 Connie Young Yu. 1981.“A History of San Francisco Chinatown Housing.” Amerasia Journal. 8 (1): 93-110

7 Haitung King and Frances B. Locke. 1987. “Health Effects of Migration: U.S. Chinese in and outside the Chinatown”. International Migration Review. 21 (3): 557.

8 Scott R. Baxter, “The Response of California’s Chinese Populations to the Anti-Chinese Movement”, 31.

9 Connie Young Yu, “A History of San Francisco Chinatown Housing.” 97.

10 Scott R. Baxter, “The Response of California’s Chinese Populations to the Anti-Chinese Movement”, 31.

11Scott R. Baxter, “The Response of California’s Chinese Populations to the Anti-Chinese Movement”, 31.

12 David, Hathaway and Stephanie Ho, “Small but Resilient”, 45.

13 David Hathaway and Stephanie Ho, “Small but Resilient”, 46.

14David Hathaway and Stephanie Ho, “Small but Resilient”, 56.

15David Hathaway and Stephangie Ho, “Small but Resilient”, 49.

16 P. Ruskin. “Pungent Chinatown.” New York TImes (New York City), September 26,1981, Opinion. Accessed May 9, 2014. thp://www.nytimes.com/1981/09/26/ opinion/l-pungent-chinatown-027834.html.

17 “The City is Picking Up Garbage in Chinatown.” 1981.New York Times (1923-Current File), Dec 16, 1. http://ezproxy.macalester.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/121633749?accountid=12205.

18 “The City is Picking Up Garbage in Chinatown.”

19 Anthony Ramirez, “In Chinatown, Ugly Trash, but a Pretty Place to Put It.”New York Times (New York City, NY), April 1, 2006. Accessed April 20, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/01/nyregion/01chinatown.html.

20 Diana Pei Wu. 2011. “Asian Pacific Islanders Made Statistically Invisible”. Race, Poverty &Amp; the Environment. 18 (2): 62.

21 Ming Wen, Diane S. Lauderdale, and Namratha R. Kandula. 2009. “Ethnic Neighborhoods in Multi-Ethnic America, 1990–2000: Resurgent Ethnicity in the Ethnoburbs?” Social Forces. 88 (1): 425-460.

22 T., Lee, D. Brugge, C. Francis, and O. Fisher. 2003. “Asthma Prevalence Among Inner-City Asian American Schoolchildren”. Public Health Reports. 118 (3): 215.

23 T. Lee, D. Brugge, C. Francis, and O. Fisher, “Asthma Prevalence”, 216.

24 T. Lee, D. Brugge, C. Francis, and O. Fisher, “Asthma Prevalence”, 216.

25 T. Lee, D. Brugge, C. Francis, and O. Fisher, “Asthma Prevalence”, 216.

26 Connie Young Yu, “A History of San Francisco Chinatown Housing.” 100

27 Julie Sze, “Asian American activism for environmental justice”. 149.

28 M. Gaydos , R. Bhatia, A. Morales, P.T. Lee, et al. 2011. “Promoting health and safety in San Francisco’s Chinatown restaurants: Findings and lessons learned from a pilot observational checklist”. Public Health Reports. 126 (SUPPL. 3): 62.

29M. Gaydoes et al. “Promoting health and safety in San Francisco’s Chinatown restaurants” 64.

30 Julie Sze, “Asian American activism for environmental justice”, 154.

31 T. Gilmore, GF O’Malley, WB Lau, DR Vann, A Bromberg, A Martin, A Gibbons, and E Rimmer. 2013. “A comparison of the prevalence of lead-contaminated imported Chinese ceramic dinnerware purchased inside versus outside Philadelphia’s Chinatown”. Journal of Medical Toxicology : Official Journal of the American College of Medical Toxicology. 9 (1): 17.

32 T Gilmore, “Lead-contaminated imported Chinese ceramic dinnerware,” 18.

33 Julie Sze, “Asian American Activism for environmental justice,” 154.

34 Khin Thein, Kyaw Thuya Zaw, Rui-Er Teng, Celia Liang, and Kell Julliard. 2009. “Health Needs in Brooklyn’s Chinatown: A Pilot Assessment Using Rapid Participatory Appraisal”. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 20 (2): 379.

35 Khin Thein, K T Zaw, R Teng, C Liang, and K Julliard, “Health Needs in Brooklyn’s Chinatown,” 381.

36 Khin Thein, K T Zaw, R Teng, C Liang, and K Julliard, “Health Needs in Brooklyn’s Chinatown,” 384.

37 Khin Thein, K T Zaw, R Teng, C Liang, and K Julliard, “Health Needs in Brooklyn’s Chinatown,” 384.

38 Khin Thein, K T Zaw, R Teng, C Liang, and K Julliard, “Health Needs in Brooklyn’s Chinatown,” 385.

39 Julie Sze, “Asian American Activism for environmental justice” 153.

40David Hathaway and Stephangie Ho, “Small but Resilient”, 47.

41 Min Zhou and John R. Logan. 1991. “In and out of Chinatown: residential mobility and segregation of New York City’s Chinese”. Social Forces. 70.

42Min Zhou and John R. Logan, “In and out of Chinatown,” 75.

43Mosenkis, Jeffrey. “Finding the bamboo ceiling: Understanding East Asian barriers to promotion in US workplaces.” PhD diss., THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO, 2011.

44 Mae Lee, 2004. “Clearing the Air in Chinatown: Asthma advocacy stems from resident-driven research”. Race, Poverty &Amp; the Environment. 11 (2): 41.

45Chinese Progressive Association. Last modified 2008. Accessed May 5, 2014.

http://www.cpanyc.org/About%20us.htm.

46Mae Lee.,“Clearing the Air in Chinatown,” 41.

47Mae Lee.,“Clearing the Air in Chinatown,” 41.

48Mae Lee.,“Clearing the Air in Chinatown,” 42.

49 Julie Sze, “Asian American activism for environmental justice”. 151.

50 Julie Sze, “Asian American activism for environmental justice”. 151.

51 Julie Sze, “Asian American activism for environmental justice”. 152.

52 Julie Sze, “Asian American activism for environmental justice”. 151.

53 Julie Sze, “Asian American activism for environmental justice”. 153.